The Golden Trezzini Awards juror talks about how the famous monument to the first great architect of St. Petersburg was created, and other things.

Picture by Yuri Molodkovets

Pavel Ignatyev, St. Petersburg-based sculptor and restorer, belongs to a creative dynasty. His parents Pyotr and Irina Ignatyev were artists, his grandfather Alexander Ignatyev and his grandmother Lyubov Kholina were sculptors, his maternal grandfather Patvakan Grigoryants and his great-uncle Vladimir Sudakov worked as graphic artists.

Pavel Ignatyev was born in 1973 in Leningrad. He is the author of many pieces of art: the statue of Academician Likhachyov in the Twelve Colleges Building; Prof. Maxim Kovalevsky’s bust outside the Sociology Dept. of the St. Petersburg State University; commemoration boards to writer Eugeny Schwartz and ballerina Galina Ulanova. Mr. Ignatiev restored façade sculptures of the Bobrinsky Palace and the Admiralty Building. The Swiss town of Locarno can boast a memorial plaque to Mikhail Bakunin made by the sculptor, and his monument to the first St. Petersburg architect Domenico Trezzini is located on the Vasilievsky Island of St. Petersburg.

— Trezzini Monument was erected in 2014, and you’d been working on it since 1994. 20 long years! And eventually, for four years your Domenico has been standing proud on the University Embankment. Tourists take pictures at it, teenagers meet up at its pedestal. There is no doubt that it has become a landmark not only of the Vasilievsky Island, but of St. Petersburg in general. Has it lost its connection with you, its creator?

— It definitely hasn’t. I am surprised that it has become so popular. They are telling myths about it already, and dedicate poems to it. And naturally, they send those poems to me. Quite recently Trezzini’s descendents from the Swiss Canton of Ticino, where he originally hailed from, came to see the monument.

— Did they like it?

— They did. Actually, they have been familiar with it for quite a while. They even possess one of my early sketches, which I gave them. Of course, I also visited Switzerland to see “Trezzini-related places.” Today, several families bearing this surname reside there. They say, the name comes from the Tresa river running along the Swiss-Italian border. A city on this border is called Ponte Tresa.

By the way, there are Trezzini’s relatives living in Petersburg, too: the Lemans and the Tchernovs, the latter descending from the reputed Decembrist.

— Does it mean that the landscape at the monument’s pedestal was modeled from life?

— Nearly so. You know, he originally came from the Astano village in Ticino. Nothing has really changed there in over three hundred years. Glorious landscapes, mountains, and lakes, but everything there is so scaled-down. They have nothing like our architecture. Nowhere there is a sign that a son of these lands built St. Petersburg. It is amazing how that region, as Alexander Benois has put it, gave birth to an abundance of famous architects who build half Europe. Just imagine, over six hundred names! Many of them earned more fame than our Trezzini, but none of them had a chance to build an imperial capital from scratch. I believe many would have considered taking Trezzini’s place if they had been given a choice.

— Let’s go back to the monument. How many models have you made in these 20 years, and at what stage did Domenico drape his famous fur coat around his shoulders?

— The fur coat has been there from the very start. However, there were many models, indeed, each with its own mood. I’ve made a special calculation recently: over these years I made 10 Trezzinis. They were from 0.6 to 5.5 m high, and of course, not all of them survived. I actually miss the first one most of all. It was a sketch model for my diploma, 0.6 m high. It was destroyed by a cleaner, there’s nothing left.

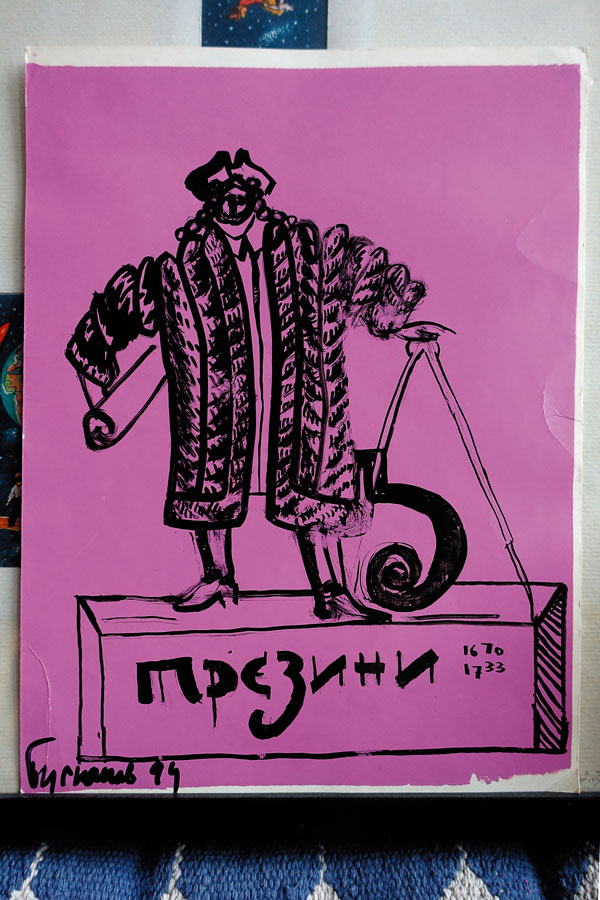

Domenico Trezzini monument, sketch. Pavel Ignatiev, 1994

— Destroyed? Do you mean, on purpose?

— Well, the day was coming to an end, and the clay we had been using was to be returned to the baths. Being young and silly, I had been messing around for about three days, I believe. And when I returned, it was gone. At that time, we didn’t have any snapshot cameras or smart phones, and there was not even a photo left. Then there was another good one, two meters high, which I made for my diploma. It fell down on the workshop floor and got flattened over it. Later, there appeared a customer eager to provide funds for Trezzini’s monument to be erected, and I made a three meters high one. However, the customer lost his interest later, and the erection to mark the city’s 300th anniversary was cancelled, so I destroyed and the sculpture, almost finished, that time – on my own.

If I could bring all of them, both big and small ones, together, they would seem alike from a distance: each of them wearing a fur coat, with a roll of drawings in one hand and a pair of compasses in the other. Yet, if looked closely at, they were all different, and in its time, each one meant a lot to me.

The thing is that for all these years my mind was occupied with not only Trezzini, but with Petrine Baroque at large. I studied architecture, and music, and costumes. For five years I worked in the Summer Garden, close to the Peter’s Palace built by Trezzini, and I travelled around Europe to study Baroque monuments.

— And you never got fed up with Baroque?

— Sometimes I definitely felt so. At some points, I felt that I couldn’t go on, that I was about to abandon this Trezzini’s thing forever. I have this album, Russian Art of the Petrine Era, and you know, I got rid of it three times. However, moving forward, I woke up thinking, “Well, not yet… I’ve got to make one more Trezzini.” And I couldn’t help but go to the bookstore to get just the same album.

When I was working on my first Trezzinis, I hadn’t been to Stockholm or Copenhagen yet, I hadn’t seen any of the things that Trezzini was inspired by when creating the Petrine Baroque. Actually, it is not just about my experience – over these years our expertise in Baroque has widened. For instance, the Early Music Festival got us acquainted with the Baroque music. Naturally, the music of that time affected movements and posture of people, along with theatre, costumes, horse riding, and fencing. Not knowing what gesture they used to take a letter out of the inner pocket of their camisole, I wouldn’t have got right the posture that Trezzini could have taken if I had to model him from life.

It must be mentioned, too, that my Trezzini is not a Petrine Baroque-style monument, not some emulation, but more of reflexion, it’s my story about Baroque, in which I speak of this style as monotonous, ponderous, and yet melodious.

— That’s extremely interesting. What project are you working on now? Has it got anything to do with Petrine Baroque, too?

— No, it’s completely different. Now, together with the Street Art Research Institution I am working on an urban sculpture that is to be erected in Almetyevsk, Tatarstan. That is a rather surrealistic image: Gabdulla Tuqai, a Tartarian poet, is riding a bicycle, Shurale, a small wood spirit from fairy tales, looking out of his basket. The project curators have agreed that the sculpture can’t be demonstrated prior to installation. Its future location is also kept in secret.

— Thank you for joining the Golden Trezzini Awards jury. Special thanks for your intent to award the winner of the category going by the code name “For Best Combination of the Piece of Art and the Interior” with a special sign you’ve made. Who do you want to award with this special prize?

— I’d like to give it to the nominees who use original pieces of art when decorating residential and public interiors. I mean, not stucco molding or cliché painting, but original works of art, both old and contemporary ones.

Today, matters of art pieces are often addressed when an expensive design project is already completed and furniture is in its places. This is where the client says, “Let’s put something on the wall here.” At this point both the architect/designer and the client are psychologically exhausted and tired. Normally, no one feels able to choose a true piece of art, a picture, not a poster, leave alone something better. Of course, there are some connoisseurs among clients. They attend galleries and auctions, and they can tell the designer, “Take this art piece as a starting point and try to make an interior to match.”

There is a well-known anecdote about Disney. Some composer brings him a music recording for a cartoon. Disney listens to it, then turns it off, and puts on Beethoven. And he tells the composer, “Do you feel the difference? Try harder.” And I believe, this ‘try harder’ is really important.

I will be glad if the prize I’ve established helps to gradually change today’s customers’ attitude to choosing art pieces for their interiors.

By Pavel Tchernyakov